The human brain is wired with natural checks and balances that control negative emotions, but breakdowns in this regulatory system appear to heighten risk of violent behavior, according to findings of a study by UW–Madison psychologist Richard Davidson.

As part of a special report on violence in the July 28 issue of the journal Science, Davidson and colleagues analyzed brain imaging data from a large, diverse group of studies on violent subjects and those predisposed to violence. The studies focused on people diagnosed with aggressive personality disorder, those with childhood brain injuries and convicted murderers.

Researchers found common neurological threads among these more than 500 subjects in the brain’s inability to properly regulate emotion. The study focused on several interconnected regions in the prefrontal cortex of the brain, areas defined in Davidson’s previous work as an essential control mechanism for negative emotions.

A similar brain process has been implicated in a number of mental health problems, including depression and anxiety disorders. Davidson says this newfound connection between violence and brain dysfunction opens a new avenue for studying and possibly treating violence and aggression.

“We are placing the question of violence right in the middle of our basic research on the neurobiology of emotion, because our previous insights in this area give us tremendous leverage to understand the root causes of violence,” Davidson says. “There never has been a theoretical framework to make sense of this before.”

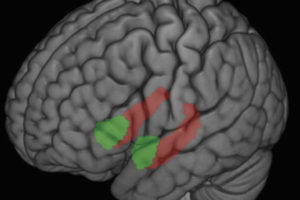

One of the core findings, Davidson says, deals with the interplay between several distinct brain regions, namely the orbital frontal cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex and the amygdala. The orbital frontal cortex plays a crucial role in constraining impulsive outbursts, while the anterior cingulate cortex recruits other brain regions in the response to conflict. The amygdala, a tiny but highly influential portion of the brain, is involved in the production of a fear response and other negative emotions.

Davidson and colleagues Katherine Putnam and Christine Larson found that normal brain activity in the orbital and anterior regions were blunted or entirely absent in many of the study groups, while the amygdala showed normal or heightened activity. The inability of the two brain regions to effectively counteract the response of the amygdala may help explain how threatening situations can become explosive in some people.