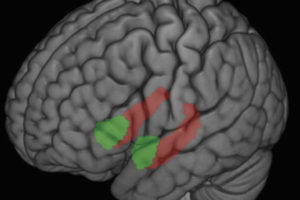

In a recent research paper published in the journal Scientific Reports, CHM Fellow Regina Lapate, Center Founder Richard Davidson and their team explored how conscious awareness of negative stimuli influence brain activity and people’s behavior. They examined how the amygdala, an area of the brain important to processing emotions, responds to negative stimuli in coordination with the prefrontal cortex, a brain region known for its role in regulating emotions.

In the study, researchers showed participants pictures of fearful faces. In one “aware” condition, participants were aware that they were seeing images of fearful faces as they viewed with both eyes. In the other “unaware” condition, researchers made the fearful faces invisible to the participants by presenting colorful squares (called “mondrians”) to each participant’s dominant eye, while fearful faces were simultaneously shown to each person’s non-dominant eye. This procedure results in participants having the experience of only seeing the mondrians. After viewing fearful faces, participants were asked to rate emotionally neutral faces they had not seen before on a likeability scale.

Consistent with earlier studies, the researchers found that when people viewed a negative stimulus such as a fearful face in both “aware” and “unaware” conditions, activity in the amygdala increased. Yet when participants were “unaware” that they viewed fearful faces, the degree of activation in the amygdala went hand-in-hand with them giving lower likeability ratings of the neutral faces. This “misattribution” of emotion did not occur when participants were “aware,” of the fearful faces, and the team discovered that the prefrontal cortex was more engaged when people were “aware” compared to when they were “unaware.”

Lapate also found that greater connectivity between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex was associated with less emotion misattribution when viewing neutral faces. This research has implications for understanding how people can develop coping strategies for facing challenging situations and how to foster awareness of emotional triggers in order to better engage areas of the brain that make exposure to negative emotion less likely to stick around.

In addition, Lapate also found a high level of variability in the structure of this prefrontal-amygdala circuitry across individuals. People with a greater structural connectivity in the white matter in the prefrontal cortex rated the neutral faces higher in likeability after viewing the negative faces, but only when they were aware of the fearful faces. This suggests that the structure of an individual’s brain may shape how a person interprets and reacts to events that happen after a negative emotional provocation. Therefore, this finding paves the way for novel interventions that may have the potential to alter that structural connection.

– Brita Larson