The experiences of millions of people have proved that antidepressants work, but only with the advent of sophisticated imaging technology have scientists begun to learn exactly how the medications affect brain structures and circuits to bring relief from depression.

Researchers at UW–Madison and UW Medical School recently added important new information to the growing body of knowledge. For the first time, they used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)–technology that provides a view of the brain as it is working–to see what changes occur over time during antidepressant treatment while patients experience negative and positive emotions.

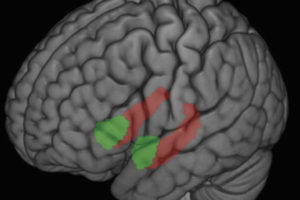

The study appears in the January issue of the American Journal of Psychiatry. UW psychology professor Richard Davidson, psychiatry department chair Ned Kalin, research associate William Irwin and research assistant Michael Anderle were the authors. The researchers found that when they gave the antidepressant venlafaxine (Effexor®) to a small group of clinically depressed patients, the drug produced robust alterations in the anterior cingulate. This area of the brain has to do with focused attention and also becomes activated when people face conflicts. Unexpectedly, the changes were observed in just two weeks.

“Conducting repeated brain scans in these patients allowed us to see for the first time how quickly antidepressants work on brain mechanisms,” said Davidson, who also is director of the W. M. Keck Laboratory for Functional Brain Imaging and Behavior, where imaging for the study took place. He noted that the findings were surprising because patients don’t usually begin noticing mood improvements until after they have been taking antidepressants for three to five weeks.