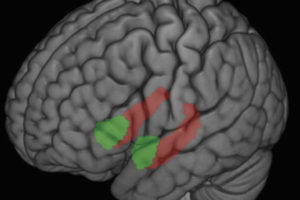

The brain’s emotional center is unusually small in autistic males with the most severe behavioral impairments, University of Wisconsin—Madison researchers reported this month.

The new study, appearing in the Dec. 4 Archives of General Psychiatry, represents the first direct link between the size of this brain structure, called the amygdala, and social deficits in autism, says Richard Davidson, a UW–Madison professor of psychology and psychiatry and the senior author of the report.

The cause of autism, a developmental neurological disorder characterized by avoidance of social interactions and poor communication skills, is unknown, but several studies have focused on the amygdala, a small region of the brain involved in processing fear and emotions. Researchers believe a better understanding of the biology of autism will improve development of treatment methods.

People with autism have long been known to avoid making eye contact, even with pictures of faces. Instead, they will focus on other parts of the face or look away. Yet despite being commonly recognized, this symptom is still not well understood.

“Why do autistic kids avert their gaze in the first place? What brain mechanisms are associated with that?” asks Davidson.

To address these questions, he and his colleagues, led by primary author of the study Brendon Nacewicz, combined magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with an eye-tracking device that records where subjects are looking. This method allowed them to directly relate amygdala size with how much time the subjects spent looking at the eyes of pictured faces.

They found that autistic adolescent boys and young men who spent the least time looking at eyes had smaller amygdalae than normal males. A smaller fear center also correlated with difficulty distinguishing emotional faces from neutral faces and with parental reports of childhood behavioral impairment.

“The amygdala has a role to play in some of the symptoms of autism,” says Davidson. For possible future therapies, he adds: “It provides an exciting target.”

– Jill Sakai