A cold dose of fear lends an edge to the here-and-now – say, when things go bump in the night.

“That edge sounds good. It sounds adaptive. It sounds like perception is enhanced and that it can keep you safe in the face of danger,” says Alexander Shackman, a researcher at the Center for Healthy Minds at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

But it sounds like there’s also a catch, one that Shackman and his coauthors – including Richard Davidson, UW–Madison psychology and psychiatry professor – described in the Jan. 19 edition of the Journal of Neuroscience.

“It makes us more sensitive to our external surroundings as a way of learning where or what a threat may be, but interferes with our ability to do more complex thinking,” Davidson says.

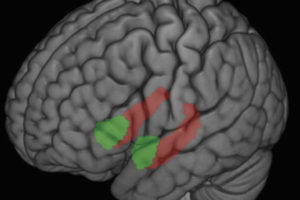

Faced with the possibility of receiving an unpleasant electric shock, the study’s subjects showed enhanced activity in brain circuits responsible for taking in visual information, but a muted signal in circuitry responsible for evaluating that information. Remove the threat of shock (and thus the stress and anxiety) and the effect is reversed: less power for vigilance, more power for strategic decision-making.

The shift in electrical activity in the brain, captured by a dense mesh of sensors placed on the scalp, may be the first biological description of a paradox in experimental psychology.