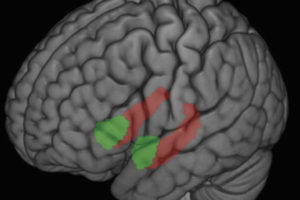

“We found that kids who had mothers with higher levels of anxiety and depression symptoms had imaging measures that are generally assumed to represent poorer white matter microstructure, perhaps reflecting less developed white matter in their brains,” says Doug Dean, a postdoctoral fellow at UW–Madison who led the analysis at the Center for Healthy Minds. “These pathways are important to healthy brain development and are known to influence mental health outcomes later in life.”

During pregnancy and in the months after birth, a dramatic reorganization of a baby’s brain takes place, as “white matter” tissue begins self-organizing and laying down pathways for connections for neurons to travel speedily through. White matter is to the brain what electrical wiring is to a computer – it helps the brain process information quickly and forms connections between areas of the brain important for everything from bodily movements to managing emotions.

In the study, researchers worked with roughly 100 expectant mothers who answered questions about their mental health during their third trimester – around 28 weeks and 35 weeks into their pregnancy. Women who participated in the study did not have a current diagnosed mental health disorder, but many experienced a range of depression and anxiety symptoms that are common during pregnancy.

Researchers were able to get a sense of women’s perceived depression and anxiety symptoms by asking the expectant mothers to respond to statements like: “I have been able to laugh and see the funny side of things;” “I have felt sad or miserable;” and “I have been anxious or worried for no good reason.”

One month after women in the study gave birth, scientists used advanced brain imaging tools – including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) – to scan the infants’ brains while they were napping.

In addition to learning that depression and anxiety symptoms were correlated with white matter development, researchers also reported distinct associations with maternal depression and anxiety symptoms and white matter in male and female infants. These results suggest that white matter development may be differentially sensitive to early life experiences in boys and girls, perhaps because boys’ white matter can take longer to develop, Dean says.