Stress may affect brain development in children – altering growth of a specific piece of the brain and abilities associated with it – according to researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

“There has been a lot of work in animals linking both acute and chronic stress to changes in a part of the brain called the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in complex cognitive abilities like holding on to important information for quick recall and use,” says Jamie Hanson, a UW–Madison psychology graduate student. “We have now found similar associations in humans, and found that more exposure to stress is related to more issues with certain kinds of cognitive processes.”

Children who had experienced more intense and lasting stressful events in their lives posted lower scores on tests of what the researchers refer to as spatial working memory. They had more trouble navigating tests of short-term memory such as finding a token in a series of boxes, according to the study, which will be published in the June 6 issue of the Journal of Neuroscience.

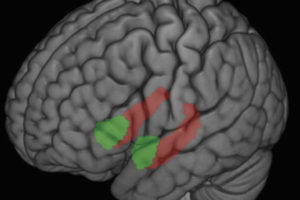

Brain scans revealed that the anterior cingulate, a portion of the prefrontal cortex believed to play key roles in spatial working memory, takes up less space in children with greater exposure to very stressful situations.

“These are subtle differences, but differences related to important cognitive abilities” Hanson says.

But they maybe not irreversible differences.

“We’re not trying to argue that stress permanently scars your brain. We don’t know if and how it is that stress affects the brain,” Hanson says. “We only have a snapshot – one MRI scan of each subject – and at this point we don’t understand whether this is just a delay in development or a lasting difference. It could be that, because the brain is very plastic, very able to change, that children who have experienced a great deal of stress catch up in these areas.”

The researchers determined stress levels through interviews with children ages 9 to 14 and their parents. The research team, which included UW–Madison psychology professors Richard Davidson and Seth Pollak and their labs, collected expansive biographies of stressful events from slight to severe.

“Instead of focusing in on one specific type of stress, we tried to look at a range of stressors,” Hanson says. “We wanted to know as much as we could, and then use all this information later to get an idea of how challenging and chronic and intense each experience was for the child.”