Brain tests at UW–Madison suggest that autistic children shy from eye contact because they perceive even the most familiar face as an uncomfortable threat.

The work deepens understanding of an autistic brain’s function and may one day inform new treatment approaches and augment how teachers interact with their autistic students.

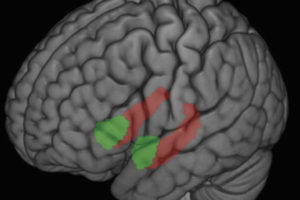

Tracking the correlation between eye movements and brain activity, the researchers found that in autistic subjects, the amygdala — an emotion center in the brain associated with negative feelings — lights up to an abnormal extent during a direct gaze upon a non-threatening face. Writing in the March 6 issue of the journal Nature Neuroscience, the scientists also report that because autistic children avert eye contact, the brain’s fusiform region, which is critical for face perception, is less active than it would be during a normally developing child’s stare.

“This is the very first published study that assesses how individuals with autism look at faces while simultaneously monitoring which of their brain areas are active,” says lead author Kim Dalton, an assistant scientist at UW–Madison’s Waisman Laboratory for Brain Imaging and Behavior. Dalton measured eye movements in conjunction with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a sophisticated technology that allows researchers to “see” a brain in action.

Notably, the UW–Madison study overturns the existing notion that autistic children struggle to process faces because of a malfunction in the fusiform area. Rather, in autistic children the fusiform “is fundamentally normal” and shows only stunted activity because over-aroused amygdalas make autistic children want to look away, says senior author Richard Davidson, a UW–Madison psychiatry and psychology professor who has earned international recognition for his work on the neural underpinnings of emotion.

“Imagine walking through the world and interpreting every face that looks at you as a threat, even the face of your own mother,” Davidson adds. Scientists have in the past speculated that the amygdala – which has been implicated in certain anxiety and mood disorders – plays a role in autism, but the study directly supports that idea for the first time.