Lying, fighting with others and acting disobediently are behaviors sometimes seen in preschool classrooms, but what sets the brains of children who behave this way apart from those who don’t?

That’s a question Jessica Caldwell, Center for Healthy Minds collaborator and clinical neuropsychologist at Upper Peninsula Health System-Marquette, set out to answer by unearthing links between early-life behaviors and the size of certain brain structures later in adolescence.

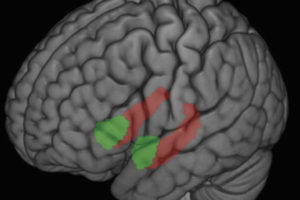

She and colleagues found that boys with a higher level of these externalizing behaviors in preschool had key brain structures that were smaller in volume later in life.

“Behavior in preschool, even normal variations in behavior in preschool, can have really important relationships with the structure of our brains later in life,” Caldwell says. “And then during adolescence, this is a time when we know things can go very well or things can start to go badly. It’s important to learn how that relationship works between early life and early adulthood to start understanding what puts some at risk and what protects others from mental illness.”

In the study, first published in the journal PLoSOne, she and colleagues examined data from the Wisconsin Study of Families and Work. Specifically, they examined externalizing behaviors in 76 male and female preschoolers, who later participated in a brain scan at 15 years of age. Focusing on images of the amygdala, prefrontal cortex and hippocampus – all structures of the brain that help generate and respond to emotions and behaviors, Caldwell discovered trends specific to each gender.