Our brains respond swiftly to keep us safe from threats in our environment, whether it’s avoiding stepping on snake during a walk on the trails, a close encounter with oncoming traffic, or even a frightening movie scene.

Once the threat passes, most people’s bodies return to a calmer state.

But for individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), these fight-or-flight responses can be triggered more easily in situations when threats are milder or not present at all. Even more, each person may have a unique response and set of symptoms, making the disorder challenging to treat.

So why has it been so challenging to treat PTSD so it goes away? Or, perhaps more importantly, are we dealing with something far more complex?

Dan Grupe, a postdoctoral research associate at the Center for Healthy Minds at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, says part of the reason the disorder has been so difficult to treat is because the scientific and medical communities have underestimated its complexity.

He and other researchers at UW–Madison, including Center Graduate Student Joe Wielgosz, Center Founder Richard Davidson, and Associate Professor Jack Nitschke, are expanding the idea that people living with PTSD not only experience different symptoms, but can also exhibit different brain circuitry profiles during trauma.

“There’s been a lot of neuroimaging research in PTSD that has placed the disorder in these more categorical entities,” says Grupe, who led a recent study published in the journal Psychological Medicine. “It’s like you have PTSD or you don’t. In reality, it’s not that simple.”

For instance, he says, one person’s symptoms of the disorder could include a numbing response, while another experiences hyperarousal or hypervigilance when faced with a perceived threat. Symptoms are mostly identified in clusters, but the source of them – the brain’s reactions – are just beginning to be identified and understood.

Rethinking how PTSD is categorized and studied holds promise for better treatment for the 7 to 8 percent of people who experience PTSD in their lifetime. In the United States, the vast majority of people with the disorder are non-veterans; however, veterans represent a group with high rates of the disorder and an alarming rate of negative health outcomes such as depression, anxiety, and suicide.

In the study, Grupe and the team recruited 50 veterans with PTSD and examined how patterns in their brains – which circuits became active at specific points in time – differed among participants when they were exposed to a simulated threat in the laboratory.

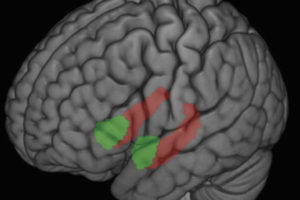

By studying the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), a part of the brain that tells other areas such as the amygdala that danger has passed, researchers can parse through whether this region is over-active, resulting in some of the hyper-aroused symptoms common to PTSD.

Essentially, the team is beginning to match symptoms to brain activity.