While poring over brain scans of a Buddhist lama, researchers noticed an intriguing pattern. The brain of monk and long-time meditator Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche, who was 41 years old at the time, looked younger than his actual age – eight years younger give or take.

The possibility that a person’s “brain-age” might be affected by meditation adds to a growing list of how mental training may yield lasting changes.

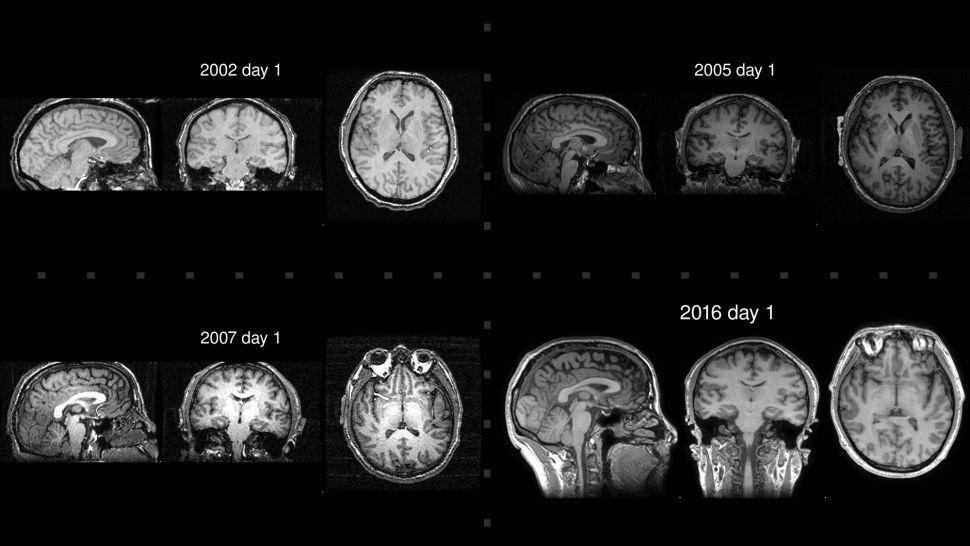

The findings, published by a team at UW–Madison’s Center for Healthy Minds and the Waisman Center in the journal Neurocase, are the first of their kind to examine a long-term meditator’s brain scans over multiple years and compare those with the scans of people from a comparison group who don’t meditate as extensively.

“It raises the possibility that meditation practice may slow the rate with which the brain ages,” says Richard Davidson, who launched the research and is the William James and Vilas Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry at UW–Madison. “This could have important implications for brain-related diseases of aging such as Alzheimer’s Disease.”

Davidson says previous studies suggest that meditation practices can be anti-inflammatory and may downregulate genes related to inflammation and aging.

It raises the possibility that meditation practice may slow the rate with which the brain ages

The research collaboration with Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche began in Wisconsin in 2002 and has influenced the way the UW–Madison team studies long-term meditators. When Davidson shared the findings, Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche was amused by them since his dedication to meditating isn’t to defy aging, but to promote insight and happiness. For both scientists and Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche, the opportunity to collaborate and unearth new insights on how the brain works has been a rewarding experience.

“Up to now, we have this ancient lineage of meditation in Buddhism, so what we believe is that everybody can transform, everybody can change,” Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche says. “So by having participated in this research, I found that through modern science, I can see this and it’s true.”

But how do brain scans of Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche, who has spent more than 60,000 hours meditating, compare to those of people who don’t meditate?

That’s the fundamental question the team tackled by studying the Buddhist monk’s brain MRI data, collected at different intervals between 2002 and 2016, together with the brain scans of more than 100 non-meditators from the Wisconsin area.

I hope that in the future, whatever discoveries and knowledge can also help people’s lives. Combining practices and scientific discoveries together might be very beneficial

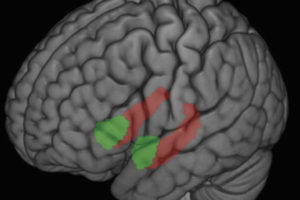

“We found that the brain aging differences seem to be arising from coordinated changes spread throughout the brain. If you look at specific regional changes using only classical statistical methods, there is no apparent difference between Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche and the comparison group,” says Nagesh Adluru, an associate scientist in the Waisman Laboratory for Brain Imaging and Behavior who led the analysis.

“Yet when our analysis considered the entire set of gray matter voxels of the brain – the processors so to speak – using a relatively novel machine learning framework, then we noticed a difference. Such analytic approaches empower researchers to discover patterns and signals from images that might not be accessible through classical approaches or even a set of trained human eyes.”

Adluru says the research is an exciting case study that combines a unique dataset and machine learning, and the results prompt further research of the longitudinal relationship between extensive meditation practice and aging of the brain using modern analytic approaches. The hope, he adds, is to potentially study other individuals who are more similar to Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche in life experience.

Analytic approaches like machine learning empower researchers to discover patterns and signals from images that might not be accessible through classical approaches or even a set of trained human eyes

In addition, what excites Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche moving forward is how collaborations between scientists and Buddhist practitioners can complement one another and influence people’s daily habits.

“What I found in discussing this with the scientists is that there is a lot of insight and discovery, but there’s not much about how to apply this in your everyday life,” he says. “In Buddhism, we have a lot of application practice – how to work with perception – how you perceive the world, how you perceive yourself, how you perceive others. These can affect your entire life, your relationships, your behavior, your job, your social circle. I hope that in the future, whatever discoveries and knowledge can also help people’s lives. Combining practices and scientific discoveries together might be very beneficial.”

Additional authors of this scientific paper include Cole Korponay, Derek Norton and Robin Goldman.

-Marianne Spoon