Mindfulness meditation – the practice of paying attention on purpose to the present moment – has garnered interest in improving a host of mental health traits, including attention and emotion regulation. But how do these practices affect a person’s impulsive behavior, like giving in to that second round of dessert?

New research from the Center for Healthy Minds at the University of Wisconsin–Madison published in the journal Scientific Reports suggests that mindfulness training in experienced meditators as well as in people new to meditation does not lower certain aspects of impulsivity.

“Impulsivity is complicated, and it can arise from any number of more fundamental underlying deficits,” says Cole Korponay, a Center for Healthy Minds collaborator who led the analysis as a graduate student and is currently a postdoctoral research fellow at Harvard University’s McLean Hospital. “Someone could display impulsive behavior because they have trouble regulating their attention, or trouble inhibiting their motor responses, or trouble with long-term planning or waiting.”

What’s important, Korponay says, is acknowledging that while some aspects of impulsivity relate to attentional difficulties and might be positively affected by mindfulness, new evidence suggests that aspects of impulsivity not associated with attention aren’t improved by mindfulness training, at least in this recent study of healthy adults.

“We were surprised because, given its emphasis on remaining nonreactive and observant towards one's emotions and thoughts, we expected mindfulness training to be associated with reduced impulsivity in people new to the practice as well as in experienced meditators,” he says. “We discovered that neither short-term nor long-term meditation appears to be effective for reducing impulsivity related to motor control and planning capacities.”

"We were surprised because, given its emphasis on remaining nonreactive and observant towards one's emotions and thoughts, we expected mindfulness training to be associated with reduced impulsivity in people new to the practice as well as in experienced meditators. We discovered that neither short-term nor long-term meditation appears to be effective for reducing impulsivity related to motor control and planning capacities."

In several earlier studies, findings showed that people’s higher self-ratings of mindfulness were correlated with lower self-ratings of impulsivity, but those studies did not look at behavior or examine whether mindfulness training could causally reduce impulsivity. This is the first analysis of its kind to assess the effect of mindfulness training on different aspects of impulsive behavior and its neural correlates in both novice and expert meditators, Korponay says.

These early findings bear relevance to determining whether mindfulness may be a viable treatment option for individuals living with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) or addiction disorders, where impulsivity plays a significant role.

In the new research, the team compared four groups of people over the course of eight weeks and beyond, including experienced meditators with on average 9,000 hours of practice, people who are new to meditation who participated in a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) course, people who are new to meditation who participated in a health program that did not include mindfulness, as well as a control group that received no intervention.

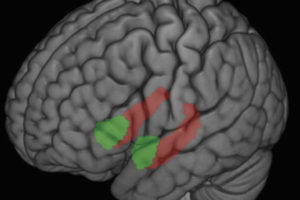

The groups completed a variety of tasks in the lab, including a motor test where they were asked to press or not press a button upon hearing specific sounds, which is intended to measure motor impulsivity. In addition, researchers looked at structural MRI scans to assess brain volume at different areas that are related to impulsive behavior as well as resting state functional MRI, which gives scientists a better idea of functional networks in the brain that are related to impulsive behavior.

The team found no significant differences in impulsivity behaviors or in brain structure or function between the mindfulness training group and the control groups after the intervention, suggesting that mindfulness might not be the best path forward for healthy adults who want to improve non-attentional aspects of impulsive behavior. Though the experienced meditators showed differences compared to non-meditators in key brain regions related to impulsivity, researchers did not have the evidence to suggest that mindfulness training was the reason for these differences, and other factors may be at play.

Understanding exactly how mindfulness practices work, for whom, and why, remains a challenge.

“It’s possible that mindfulness meditation might work for one person whose impulsivity arises out of one pathway of behavioral and neural dysfunction,” says Korponay. “But that might not be the case for everyone. Every person's overall level of impulsivity derives from different percentages of attentional impulsivity, motor impulsivity and non-planning impulsivity. It differs a lot from person to person and from disorder to disorder.”

In addition, researchers say it’s important to note that this study applies only to very specific circumstances and studies only one form of meditation of many in healthy adults and not in youth or in adults who may react differently, including people with ADHD and addiction disorders.

"It is important to understand that meditation is not helpful for everything and that identifying the specific domains for which it may not be helpful is important."

“This is one of a series of publications from our Center that reports null effects of meditation on a specific outcome where we hypothesized there would be an effect,” notes Richard Davidson, the senior author of the study and director of the Center for Healthy Minds. “It is important to understand that meditation is not helpful for everything and that identifying the specific domains for which it may not be helpful is important. Having said this, it is important to recognize that since our study was conducted in people without any specific disorder, it is possible that those with more impaired impulsivity would show benefit from these practices, though this is a question that requires further study.”

-Marianne Spoon