We hear it all the time: “Take a deep breath.” It’s a tactic that’s been known to calm the mind – and body – in many contexts and cultures, but learning the science behind how breathing affects psychological well-being remains an open area for investigation.

In meditation, for instance, certain mindfulness practices encourage people to cultivate awareness of their own breath and other bodily sensations. Figuring out the biological consequences of this behavior served as the focus of Center Graduate Student Joseph Wielgosz in a recent paper published in Scientific Reports.

Wielgosz and colleagues found that people who’ve racked up extensive meditation experience – called “long-term meditators” – consistently showed a lower respiration rate when not meditating compared to a control group of people with no experience meditating. Respiration rate is the number of in and out breaths a person has per minute.

“We’ve suspected this for a long time, but what this helps confirm is the idea that extended mindfulness training is not just training one’s cognitive processes, but it also appears to be training and retraining the body as well in ways we’re just beginning to understand,” Wielgosz says.

He adds that previous studies have typically looked at respiration while participants were performing specific meditation practices. In contrast, the new analysis looked at respiration rates when the participants were simply sitting and relaxing in the laboratory, a situation more likely to reflect their breathing patterns in everyday life. The study also used data collected over multiple sessions to confirm that the relationship between practice experience and respiration rate holds up consistently over time.

"...extended mindfulness training is not just training one’s cognitive processes, but it also appears to be training and retraining the body as well in ways we’re just beginning to understand."

He and colleagues were surprised to discover that lower respiration rate was not predicted by the amount of daily practice, but rather by intensive retreat practice where people spent an entire day or multiple days in a more secluded setting dedicated to meditation. This trend existed even when the team controlled for health and physical factors like age, height, weight, resting heart rate and blood pressure.

The analysis found that overall, long-term meditators showed respiration rate of 1.6 fewer breaths per minute than the control group of non-meditators. Among the long-term meditators, doubling in the number of hours spent on intensive retreat was associated with a decrease in respiration rate of 0.7 breaths per minute.

“The takeaway is that where you do your practice and how you do your practice matters,” he says. “So all mindfulness training isn't created equal, and that's something that the field’s only just starting to look at. It’s good food for thought in your own practice and something to pay attention to.”

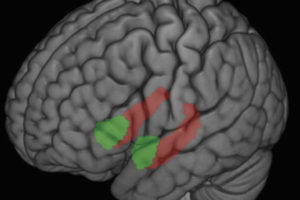

The next steps in this work include investigating whether differences in breathing rate relate to changes in the meditators’ emotional experience, using brain imaging data. For example, past work suggests that breathing patterns can influence how we experience physical pain. Do experienced meditators use breathing as a tool to regulate their emotions, in their daily lives?

By looking at how mindfulness practice trains the body as well as the mind, Wielgosz and colleagues hope their continued work will help us get more precise in understanding how, why and when contemplative practices can benefit emotional health and well-being.

– Marianne Spoon