The scientific study of emotion, an area once considered too “soft” for serious inquiry, is developing a solid future at UW–Madison.

This fall, a team of UW–Madison researchers studying emotions and health have received three grants totaling more than $6 million over the next five years. The researchers say this new infusion of support is helping make UW–Madison one of the premier places to study the complex interplay between emotions and biology.

“When I first started talking about all this, I was regarded as somewhat of an oddball in advocating the neuroscience of emotion,” said psychologist Richard Davidson, one of the leaders in the field. “The view was that emotions were too ephemeral to be approached scientifically.”

No one doubts the field’s potential any more. In fact, researchers are finding striking connections between emotions and health. For example, a recent study found that heart attack patients who become depressed are five times more likely to die than those who do not.

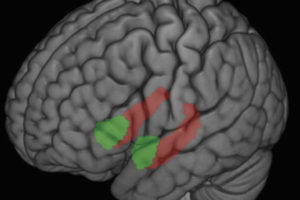

Studies at UW–Madison are identifying the brain’s “processing centers” for negative and positive emotions. Other studies focus on a fear-regulating portion of the inner brain called the amygdala. Researchers are finding that abnormal function of these key emotional centers can trigger psychological problems.

Davidson said the field is being energized by new technology in brain imaging, which is allowing people to literally peer into the working brain. A large base of animal research is also laying a foundation for work with human implications.

Work being done at UW–Madison is under the Wisconsin Center for Affective Science directed by Davidson and the Health Emotions Research Institute, which is co-directed by Davidson and psychiatrist Ned Kalin. Other core members of the research team include psychologist Hill Goldsmith and psychiatrist Marilyn Essex.

Davidson said the group hopes to establish a baseline for normal emotional development, which will help them identify problems and intervene before psychological problems occur. “Emotion is the key variable in understanding all forms of mental illness,” he said. “If we can better specify who might be vulnerable, we can intervene much earlier in the life span.”

The team has reason to be blissful about the future of emotion studies here. The National Institute of Mental Health provided researchers with a $3.7 million, five-year center grant and another $1.5 million over five years to train new graduate and postdoctoral students.

Davidson said the program has hired eight new pre-doctorate and two new post-doctorate students so far this year. “Most people who are studying the brain ignore the body, and vice versa,” he said. “The goal is to educate a new generation of emotion scientists with a broader range of expertise, including psychology, sociology and biology,” he said.

A third grant of $1.25 million from the Keck Foundation will help create a new brain imaging facility at the Waisman Center “that is truly unique in the world,” Davidson said. The facility will combine two different technologies that can track both the structure of the brain and the various biological and chemical processes at work.

The resolution will be so precise, Davidson said, scientists will be able to perceive changes in very small areas of the brain never examined before. It will be especially valuable in studying the amygdala, which serves as a central processing center for fear.

Looking ahead, Davidson said he plans to devote more study to why some people have a persistent reaction to stress. “Some people are not able to turn off a negative emotion once it’s been turned on by the amygdala,” he said. In many people, this is the hallmark of anxiety disorders and creates a “vicious feedback loop,” causing both emotional problems and physical damage to the immune system and the brain.

Other research projects include:

- A project led by Kalin has developed a primate model for human fear and anxiety. The researchers are working with monkeys that have excessively fearful dispositions, and finding parallels with humans. “We think that this research will tell us a lot about the factors behind why some people develop anxiety and depressive disorders,” Kalin said.

- A study that will gauge the effects of group therapy for women who are recovering from breast cancer. The study follows a Stanford University finding that group therapy has the potential to double the survival time of breast cancer patients. The study will look at physiological measures that can explain why group therapy has this powerful benefit.

- An ongoing study of twins, led by Goldsmith, will attempt to identify children at risk of developing problems such as anxiety, social withdrawal and depression. One intriguing question is whether researchers can identify parts of the brain that regulate our temperament, such as shyness, boldness or fearfulness.