Babies’ brains undergo dramatic changes in the womb and during the first months of life, yet not much is known about how the mental health of expectant mothers shapes the brain development of their infants.

This gap in knowledge has inspired new research at the Center, which has begun to study the relationship between depression and anxiety symptoms in expectant mothers and how those symptoms are related to their infants’ brain development.

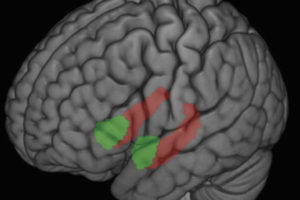

The brain can be thought of as a computer of sorts, with hardware, software and lots of wiring. The brain’s wiring — called “white matter” — forms connections needed for neurons and other signals to move quickly through different areas of the brain. At birth, babies don’t have much white matter, but after birth, white matter development explodes, making the first months after birth a critical time for brain maturation.

Early results from the Center’s research suggest that mental health symptoms of mothers during pregnancy may affect the quality of white matter development in their infants’ brains well after birth.

“The most surprising aspect of these studies is that we are beginning to see that brain development doesn’t just happen after birth and that we can influence those very early processes of brain development still in utero,” says Doug Dean, a postdoctoral research associate leading the work. “As a result, we can better understand how the brain develops.”

“The most surprising aspect of these studies is that we are beginning to see that brain development doesn’t just happen after birth and that we can influence those very early processes of brain development still in utero.”

Dean and scientists on the team are also finding that the areas of the brain where white matter is affected the most — like the superior longitudinal fasciculus, critical for establishing connections with brain regions involved in various cognitive and emotional processes — are the same areas negatively affected by depression and anxiety later in life.

The team hopes to learn whether interventions, including mindfulness-based training, could affect mothers’ symptoms and babies’ brain development. These brain areas have been shown to play a role in negative reactivity, emotional and behavioral difficulties, lower verbal IQ and even physical health problems later in life.

The findings — originally supported by the National Institute of Mental Health — fit into a larger, more comprehensive view on children’s well-being investigated by Center scientists and faculty. Tackling everything from maternal mental health to how poverty affects the developing brain, our researchers are exploring how to set the best possible trajectory for kids.

–Marianne Spoon