Research has shown that children have an innate tendency to share with others early in life. Do children share less as they get older, or do they just share differently?

Recent results published in Frontiers in Psychology point to evidence of increased cognitive complexity as children grow up that can be used to either help or discriminate against others, depending on how those capacities are channeled.

Sharing is one of the most important expressions of prosocial behavior and is linked to emotional well-being. Researchers wanted to know how this behavior varies across childhood and in what circumstances children give more or less.

Research at the Center compared the responses of 46 preschoolers and 52 fifth graders on two social decision-making tests. The first test focused on how a child’s age affects his or her sharing behavior and whether sharing and prosocial behavior could be different based on the child’s perception of the person with whom they were sharing.

Each child was presented with images of four other children – two of whom he or she knew and had identified, one a good friend and the other someone who was known but the child didn’t like to play with. The other two were unfamiliar to the participating children, representing another child who appeared to be ill (a needy other) and another who was a stranger. Children in the study were given 10 stickers and told they could keep as many as they wanted for themselves and give as many as they wanted to kids in these different groups on separate trials.

Researchers found that the preschool-aged children shared more uniformly with all groups - including kids they didn’t like. Older children gave fewer stickers to kids they didn’t like, yet they gave more than half of their stickers to a sick child – even more stickers than they gave to kids that they liked.

“It’s easy to wish well-being to those you care about, but extending that wish to those you don’t know well, or even those you find difficult, can be more challenging,” says Center collaborator and lead author Lisa Flook. “We find that older children are more selective in their sharing, which means they give more in some cases, but less in others.”

The study also noted gender differences in sharing. Boys were less likely to share than girls, by at least a sticker across the board. The tendency for girls to give more has been also seen in other research and may stem from the way societal norms place an emphasis on generosity and care-taking for girls. Yet if done to the extreme, giving and caring for others can place girls at risk for emotional problems, notes co-author Carolyn Zahn-Waxler.

In addition, researchers looked at common biases people form when they have minimal information about others. People across cultures, including children, show preference for those who experience a minor lucky event compared to a minor unlucky event. An example of this would be seeing a person finding a five-dollar bill on the sidewalk and assuming they are nicer than someone who lost a five-dollar bill out of their pocket. When someone associates circumstances with a person’s character, that bias can form the basis for developing prejudices.

In this study, children were given a small, boxed gift that they could present to another child. In one test, kids were shown a scenario where one child put money into a vending machine and received two candy bars, while another child put money in the same machine but their candy bar got stuck. The children were then asked which child they thought was nicer, and asked them which child they wanted to give their gift to.

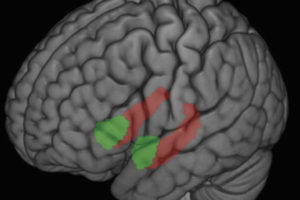

Younger children gave gifts more often to the nice, lucky kid. However, when older kids completed this task, they were more likely to give a gift to the unlucky child even if they said they thought that the lucky kid was nicer. As one possible explanation, researchers suggest that as a child’s brain develops, that child is able to make more complex decisions about how to treat others based on minimal information, and can look past initial judgements.

“Both of these sharing scenarios suggest that as we grow and deepen our cognitive development, we develop both the capacity to be more prosocial and also discriminatory. We are able to differentiate more among people and their social statuses, which can lead to more helpful yet also more harmful behavior,” says Flook. “If we can help to shape those inclinations around giving and how we perceive people, and ultimately whether we can show kindness towards people we don’t know or don’t like, this could have ramifications at a broader level. If kids are encouraged to be more prosocial, the future implications on society as a whole as these kids become adults could be significant.”

“If we can help to shape those inclinations around giving and how we perceive people, and ultimately whether we can show kindness towards people we don’t know or don’t like, this could have ramifications at a broader level. If kids are encouraged to be more prosocial, the future implications on society as a whole as these kids become adults could be significant.”

Future research could aim to uncover the underlying reasons why children make the choices they do in terms of sharing with different groups of people, and how to promote caring and prosocial behavior through classroom-based interventions throughout a child’s development.

- Sara Ifert