Mindfulness meditation has been linked to improvements in emotional and physical health outcomes in several studies over past few decades, and it’s widely taught in mental health treatment settings.

But what do we actually know about its benefits for people with specific mental health disorders?

Answering this question is the aim of a new review paper from Center for Healthy Minds experts, published in the journal Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, which provides a bird’s-eye view of the study of mindfulness for mental health disorders. The paper brings together the latest research not just on whether mindfulness is effective in different mental health conditions, but how and why.

“We now have a lot of evidence that mindfulness meditation is helpful for a range of different conditions, including depression, anxiety, substance problems and chronic pain,” says Joseph Wielgosz, a Center for Healthy Minds collaborator and postdoctoral research fellow at the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System and Stanford University. “At the same time, we also know that it’s not a universal cure-all. To make the best use of it, we need to know precisely how mindfulness meditation affects the mind and the brain, and then apply that understanding to specific conditions.”

Wielgosz says there are some areas where the evidence outpaces others. “Depression is a condition where we not only have evidence that mindfulness meditation is effective for treatment, but we have some significant evidence as to why it works.”

“We now have a lot of evidence that mindfulness meditation is helpful for a range of different conditions, including depression, anxiety, substance problems and chronic pain. At the same time, we also know that it’s not a universal cure-all.”

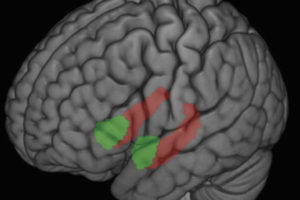

Rumination – repetitive, negative thinking about the past – is a big factor in sustaining depression, and is associated with a circuit in the brain called the default mode network. In theory, mindfulness meditation should directly target this process because people are training themselves to notice when they become lost in thought, and return their attention to the present moment. And in fact, that is what a number of studies, looking at both behavior and brain activity, seem to show.

In other areas, we still have much to learn, says Wielgosz. For example, mindfulness meditation emphasizes attention training, so we might expect it to be helpful for conditions such as attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). However, only a handful of studies have been been conducted – too few to draw any firm conclusions, researchers say.

For some other conditions, like bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, science is at an even earlier stage. Researchers are still exploring which aspects of these conditions, if any, might be usefully treated by mindfulness meditation, and what adaptations might be needed for the interventions.

The team’s review was based on a broad survey of the latest research that brought together numerous findings from different areas of mental health. These included a number of meta-analyses, which in turn summarize the effects found in individual trials and experiments.

“It’s also exciting to consider that mindfulness meditation is just one family of practices among the many to be found in contemplative traditions. The experience we have gained from researching mindfulness meditation offers us a pathway for adapting other kinds of contemplative practice into the world of mental health treatment.”

Wielgosz notes that although many mental health interventions use ideas and brief exercises based on mindfulness training, not all of them incorporate significant amounts of meditation itself. To understand the effects of mindfulness meditation practice, the team focused on interventions that include a “formal” meditation component – for example, having participants spend 30 minutes a day meditating at home.

One key priority that Wielgosz and colleagues identified for the future will be studying new ways to provide mindfulness meditation interventions for mental health treatment – for example, via smartphone apps – so that effective treatment can be available to more people. Another priority is understanding how mindfulness interventions might need tailoring across different cultural and social groups to ensure they are accessible and effective for everyone who could benefit from them.

“It’s also exciting to consider that mindfulness meditation is just one family of practices among the many to be found in contemplative traditions,” says Wielgosz. “The experience we have gained from researching mindfulness meditation offers us a pathway for adapting other kinds of contemplative practice into the world of mental health treatment.”

Other co-authors of this paper include Center faculty members Simon Goldberg, John Dunne and Richard Davidson, as well as graduate student Tammi Kral.

–Marianne Spoon