A research team, including Center for Healthy Minds scientist Sarah Short, has been awarded a $2.5 million National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD) grant to study the link between poverty and developing cognitive processes that facilitate learning, self-monitoring and decision-making in children.

Short is a co-principal investigator on this project with Cathi Propper, a senior scientist at the Center for Developmental Science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Other key personnel include Roger Mills-Koonce and Michael Willoughby, at UNC Chapel Hill and the Research Triangle Institute, respectively.

“Learning more about poverty’s effects on the developing brain and the influential factors in a child’s home environment that may serve as a protective buffer will help to us advance intervention strategies to better support families and their children.”

Sarah Short

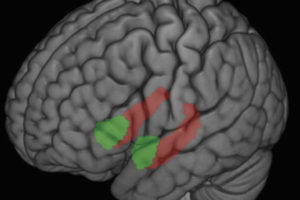

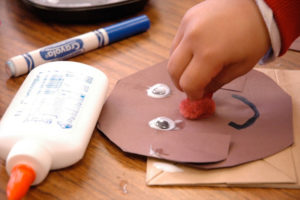

This five-year study will be the first to investigate the influence of poverty on children's brain and behavioral development over the first three years of life. The study will also focus on early experience and environmental factors that are likely to influence both brain and behavioral development. Factors that may serve to buffer the risks associated with poverty include language exposure, caregiver behavior and child sleep routines.

“Early-life experiences that occur between the prenatal period through age 3 have a major impact on children's early social, emotional, and cognitive development, as well as the neural substrates that support these abilities," says Short. “Learning more about poverty’s effects on the developing brain and the influential factors in a child’s home environment that may serve as a protective buffer will help to advance intervention strategies to better support families and their children.”

The difficulties of living in economic hardship have indeed been associated with deficits in cognitive and academic performance in children. Federal and state governments invest billions of dollars annually in programs that are intended to help “level the playing field” between children who grow up in poverty relative to their peers who do not. Traditional investments toward children in the one-to-two years prior to their enrollment in kindergarten may be too late.

Given limited public health resources, more focused investments in children’s early experiences may have a greater impact on their subsequent emotion regulation, social skills and academic opportunities. Studies such as this one have the potential to provide critical information about how the early environment affects the developing brain and whether specific experiences in the home could be targets for early intervention. The ultimate goal is to improve children’s chances for long-term well-being.

News adapted from University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill Office of Communications