At the Center for Healthy Minds, we receive thought-provoking questions and commentary from our community daily. We put a selection of questions in front of Center Founder Richard Davidson and Contemplative Expert and Center Graduate Student Cortland Dahl to tackle.

Question: Is there any research on personal electroencephalogram (EEG) or other-modality imaging in support of mindfulness training?

Richard Davidson: There’s a wealth of evidence suggesting that using EEG, functional MRI and other modalities for interrogating the human brain are helpful in understanding how various forms of meditation, including mindfulness meditation, can change the brain in ways that may be behaviorally helpful. There are two major domains where the research is strongest. One is attention regulation, where we’re learning that people’s behavior and the brain circuits important for regulating attention are altered by mindfulness meditation and other kinds of meditation. The second area is emotion regulation, through which we’ve learned that we can improve our ability to regulate our emotions, particularly to recover more quickly from negative emotion. Concerning “personal EEG” devices, there’s no scientific evidence that strongly supports them at this time.

Question: Is neurofeedback a viable asset to meditation?

Davidson: Neurofeedback is the process through which a signal associated with a particular state of the brain is provided to a person in real-time. With this signal, the person can be asked to increase the signal, which means he or she is increasing a certain pattern of activity in the brain. This approach has been used in fMRI. I would say that at this point in time, there are some scientists that believe that neurofeedback can be a useful adjunct to meditation. My own view is that it’s premature because we don’t know what the relevant signals are yet. If we fully understood what the relevant signals are, maybe neurofeedback would be more useful.

Question: Are ‘focused attention’ and ‘open presence’ mediations mutually exclusive? More generally, which meditations can be combined and which cannot?

Davidson: Focused attention and open monitoring are not mutually exclusive. It’s often the case that in a single meditation session, a person would alternate or would vary between doing a focused attention meditation and one that was more open. For example, a person may begin by focusing his or her attention on breathing, and then the field of awareness can be expanded to include thoughts and emotions, for example, before the person goes back to his or her breathing. One can fluidly go back and forth, and I think that developing the skills in one can help facilitate the other. In terms of which meditations can be combined and which cannot, I would say from a scientific perspective, we actually know very little about that.

Cortland Dahl: Within a meditation session, it can be really helpful to include different forms of meditation. One common approach is to start by cultivating compassion or by setting a compassionate motivation. So you might be doing open monitoring or focused attention, but you would start with compassion and say to yourself, “I’m doing this because I want all beings to be happy, including myself. To do that, I’m now going to meditate.”

In terms of focused attention and open monitoring, you might emphasize one or the other in particular period of practice, but both can be very helpful and bring different benefits. Focused attention is designed to stabilize attention and is especially helpful as a foundation for cultivating healthy qualities of heart and mind, and also for the practice of self-inquiry. Open monitoring also helps to stabilize attention and can be very useful in transforming the way we relate to our thoughts and emotions, especially in daily life. We can learn different practices and bring different elements in at different times, depending on what is going on in our life in the moment.

Question: If mindfulness is correlated to a specific brain function in people who practice mindfulness, can a person with epilepsy be mindful during a seizure or someone with schizophrenia during a hallucination?

Davidson: We don’t know. It’s an interesting question. I believe we actually can be mindful during certain states when it’s not commonly thought one could be mindful. One example is sleepiness, which frequently intrudes on one’s meditation (speaking from personal experience among other things). Certainly there are reports in the scientific literature that show in certain kinds of epilepsy with certain kinds of patients, the patient may become aware of the seizure before it actually becomes full-blown. So they can detect the subtle changes that may precede the full expression of the seizure. In terms of whether a person with schizophrenia can be mindful of his or her hallucinations, that’s more complicated. I don’t really think there’s any good evidence one way or the other at this time. Before someone with a serious psychological illness like schizophrenia undertakes the practice of mindfulness meditation, he or she should do it under the guidance of someone who is both a mental health professional and who knows about these meditation practices, in order to do it safely.

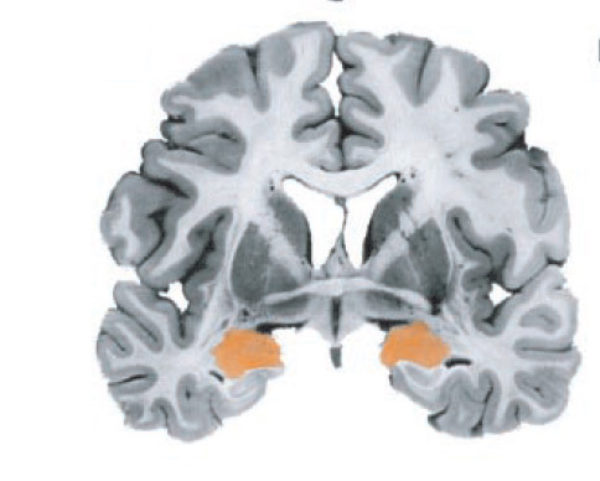

Question: How does the amygdala develop or change through the years?

Davidson: The amygdala, like any other or most other brain structures, undergoes developmental change. There are changes in amygdala volume, so the volume of the amygdala gets larger over the course of development and peaks somewhere around adolescence or late adolescence and then begins to drop off after that. We don’t really know what the functional significance of this increase in volume means at this point in time. It’s still a question around which there’s a lot of active scientific research.

Question: Does a “mindful” mind have any resemblance to a child or infant’s mind?

Dahl: There are definitely some similarities. Mindfulness creates a sense of inner simplicity. When a child walks into a forest, there is a sense of openness and appreciation – a natural curiosity about experience. Children don’t get caught up in judgments and interpretations like adults do, and they are often more interested in directly experiencing their worlds than they are in creating storylines about their experience. Mindfulness is quite similar, in the sense that a mindful mind is open and curious. Like the simplicity of a child’s mind, this state has the potential to put you in touch with the beauty and subtlety of your environment.

There are a few differences, though. For someone who is cultivating mindfulness, there’s also a feeling of recognition, of being more fully in touch with the inner landscape of thoughts, emotions and even awareness itself. In meditation, we learn to cultivate that sense of presence and openness to what is going on around us, and also to what is happening within us. A child might be full of wonder and receptivity to the environment, but not necessarily to the inner movements of the heart and mind. This difference is quite important, actually, because the heightened awareness of our own thoughts and emotions is precisely what enables us to regulate our attention, to notice when we’re getting triggered or upset, and to nurture positive thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, such as those related to kindness and compassion.